This is the first in a series of posts looking at historic hockey injuries, intended to keep me busy and you interested while we wait for October to get here.

The history was provided by Jen aka @NHLhistorygirl. Jen is a librarian and graduate student at the University of North Dakota in the last stage of her MA in history: writing her thesis on the 1972 Summit Series, media, and notions of national identity.

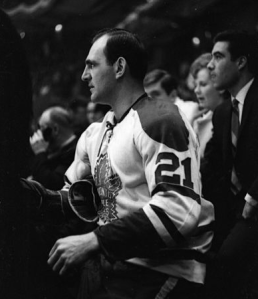

- The first all-star game: A benefit for Ace Bailey

The night of December 12, 1933 was just like any other game night at Boston Gardens. The Bruins had a two-man advantage. The Leafs sent Ace Bailey and Red Horner out as part of the penalty kill. Red checked Bruin Eddie Shore into the boards, picked up the puck, and headed for the Bruins net. Bailey moved into Horner’s defensive position near the blueline. It’s the last thing Bailey would remember about that night.

Shore mistook Bailey for Horner, and took Bailey’s feet out from under him. In an era without helmets, this was a dangerous move on Shore’s part. Bailey hit the ice head first, and began convulsing.

While Bailey’s teammates gathered around and the Boston trainers frantically tended to him, Horner punched Shore, who also hit the ice, bleeding. In the stands, a fan taunted Bailey, calling him a diver. Leafs owner Conn Smythe punched the fan, knocking teeth loose.

Bailey was awake when they took him to the dressing room, where Shore asked his forgiveness. Bailey replied, “It’s all part of the game,” before losing consciousness and falling into convulsions again. He was transported to Audubon Hospital, where he was diagnosed with a fractured skull. By morning, his condition was critical due to cerebral hemorrhaging.

He was moved to City Hospital, where neurosurgeon Dr. Donald Munro operated to relieve the cranial pressure on two different occasions. After the second surgery, the doctor pronounced Bailey’s chances as “very slim” and a priest was called to give Bailey last rites. His pulse was 160 and he had a fever of 106. Newspapers had an obituary written and waiting. Reportedly, Bailey’s nurses would slap his hand or his cheek if it appeared he was slipping away. They kept telling him his team was down two men and needed him.

His condition finally improved, though Bailey says he did not regain full consciousness for fifteen days. With his playing days over and a plate in his head, Bailey asked the league’s permission to suit up as a linesman. Worried that any hit may cause Bailey further serious damage, his request was denied and he served many years as an off-ice official for the Leafs.

- Bailey and Shore

Ace Bailey suffered what’s obviously best described as a devastating head injury. It’s amazing that he lived, even more so when you consider this happened in 1933. Penicillin had just been discovered (but wasn’t in widespread clinical use yet), and the concepts of tracheal intubation (breathing tubes) and IV anesthesia for surgery were brand new.

It’s hard to say exactly what Bailey’s specific head injury was. As such, this can really only be a look at a condition he may have had. There’s really no way to know what actually happened. We know his head hit the ice, he seized, was briefly awake and lucid, seized again, then stayed unconscious for a long time. During that period he had intracranial bleeding requiring surgical intervention, and developed an extremely high temperature.

The description of Bailey’s lucid interval could suggest he suffered an epidural bleed, which is the result of torn arteries between the skull and the dura mater (the tough covering around the brain and spinal cord). This is an uncommon type of traumatic head bleed, but made headlines in 2009 when actress Natasha Richardson died two days after a head injury sustained while skiing. She initially refused EMS care, then after a few hours was rushed to hospital with head injury symptoms and later died.

The stereotypical textbook progression of loss of consciousness-lucid interval-loss of consciousness actually doesn’t happen in most epidural bleeds. Patients can lose consciousness (or not), and may wake up (or not). The thing about the lucid interval is that’s the classic wording healthcare providers associate with the injury (and it’s extraordinarily unlikely to see it in other head bleeds).

A theory on why this happens is that the impact of the initial injury causes a loss of consciousness (from which the patient awakes), and the lucid interval represents the bleeding taking time to affect the brain as it happens between the hard skull and the relatively unyielding dura. Of course it’s important to note that this is just a theory, and the lucid interval can be of varying duration – anywhere from seconds to hours.

Why did Ace seize?

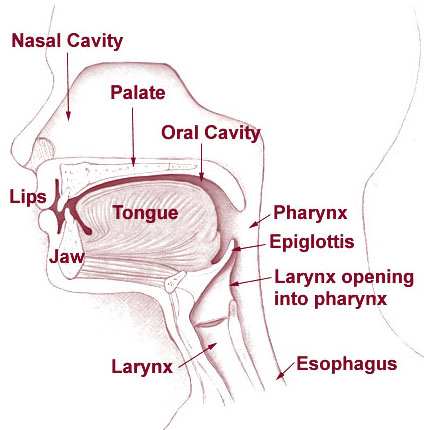

Seizures happen when the neurons in your brain aren’t firing in the nice, orderly pattern they’re used to. Seizures can be the result of a seizure disorder (like epilepsy), or an insult to the brain (like trauma, stroke, lack of oxygen, etc). In Bailey’s case, the impact of his head on the ice would have caused a cascade of events that set him up for seizure.

When his skull hit the ice, it stopped. His brain stopped when it hit the inside of the skull. The brain is a delicate thing, and it doesn’t like sudden changes. Not only would an impact with the skull likely cause a contusion (bruise) on the brain, it could potentially cause another on the other side thanks to something called a coup-contrecoup injury (French for blow-counterblow). The brain hits the skull on the side of the impact, and then in essence bounces back and hits the skull on the opposite side, causing a second contusion. Now you’ve got two areas of pissed-off brain that could misfire and cause a seizure.

Coup-Contrecoup

Treatment

Current treatment for a head injury of this type would start with transport to a trauma center. Obviously the treatment would also include the basics of pre-hospital trauma care (which I’ll grossly oversimplify here): Management of the airway with intubation if necessary, spinal immobilization, and IV fluids to replace volume loss from bleeding.

On arrival at the ER, head injured patients are often placed into the ominous-sounding medically-induced coma, which is to say they’re sedated and intubated. There are a lot of reasons this is done – for the patient’s comfort (they’re in pain, and probably scared to death), to have complete control of the airway (there’s no better airway control than having a tube stuffed into it), and for the now-controversial practice of reducing their intracranial pressure (ICP) by hyperventilating them. As we learned in this post, carbon dioxide (CO2) causes the vessels in your head to dilate, which would increase the amount of blood in there, and thus increase pressure. If you force hyperventilation, more CO2 is exhaled, reducing blood flow and therefore ICP. Hyperventilation of head injuries is falling out of favour now, as studies have shown that it doesn’t improve outcomes, and in fact can lower brain perfusion (which is bad for obvious reasons). CT scans and x-rays determine the extent of the injuries, and the patient is given IV steroids to reduce brain swelling. The patient may receive anti-seizure medications whether they’re seizing or not (to stop or prevent a seizure).

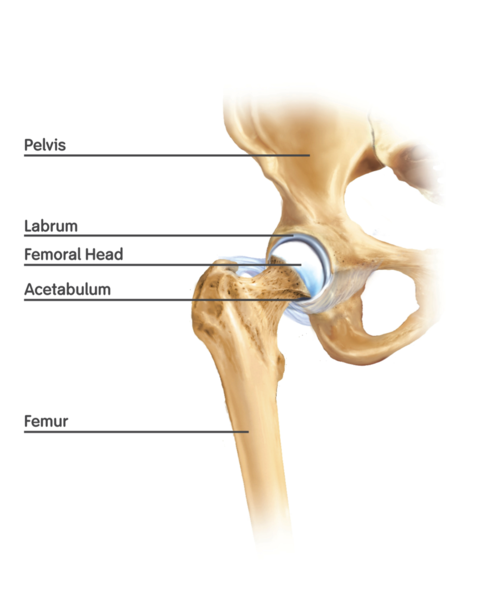

At this point the smart kids take over (that would be the neurosurgeons) and decide what sort of surgical intervention is needed. In rare cases epidural bleeds can be managed non-surgically with just steroids and observation. More often, however, the blood that’s filling the space between the skull and dura has to be taken out.

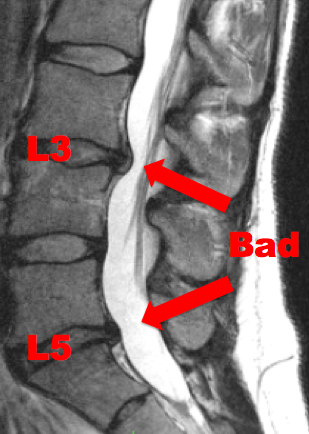

Epidural hematoma - Big red arrow provided for those who are immune to the obvious

Assuming you’re in a trauma center with neurosurgery on staff (as opposed to asleep in their golf course home with a pager on the nightstand) the treatment is craniotomy, evacuation of the blood, and ligation of the artery that’s bleeding. Translation: Take off part of the skull, suck out the blood, find what’s bleeding and tie it off. The piece of the skull may go back on at this point, or it may get stored in a fridge in the hospital basement until they’re sure the brain is done swelling and they can put it back on. If you’re in some outlying hospital with no hope of a neurosurgeon for a while, studies have shown that drilling a burr hole in the skull at the injury site is a good bridge to definitive care (yes, I saw that episode of Medical Incredible too).

As far as Bailey goes, it’s hard (impossible) to say what the two surgical procedures that he had actually were. He’s said to have had a plate in his head, which suggests fragments of his fractured skull were removed (hello, craniotomy) and replaced. Why did he have two surgeries? Good question. It’s possible the bleeding wasn’t controlled the first time, and it’s possible it was done as a staged procedure – the first surgery to take the skull fragments out, and the second to put in the plate.

Post-Surgical Complications

After his two procedures, Bailey developed a pulse of 160 and a fever of 106, neither of which is part of a healthy recovery. There are two possible reasons for these symptoms, both of which have catchy acronyms – SIRS and PAID.

SIRS – Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome

SIRS is basically whole-body inflammation. It can be a result of infection (as one might get from brain surgery in 1933), or non-infectious events (trauma, burns, severe allergic reactions, etc). In Bailey’s case it could have been either. SIRS manifests as a high heart rate, a very high or very low body temperature, rapid breathing, and a very high or very low white blood cell count (those are the ones that fight infection). SIRS is pretty common in both the medical/surgical and trauma ICUs. Generally it’s treated with symptomatic management and control (where possible) of the cause (i.e. antibiotics). In 1933 it would have been treated by cooling Bailey, and having nurses slap him to keep him from dying. Super hi tech, and apparently pretty effective.

PAID – Paroxysmal Autonomic Instability with Dystonia

PAID is a scary complication of severe head injuries where the body loses its ability to control the autonomic nervous system – that’s the one that does all the automatic things you don’t pay attention to. Things like controlling your body temperature, your heart rate, digestion, and sweating. Patients with PAID have episodes of elevations in pulse, respiratory rate, blood pressure and body temperature. They also have dystonia – episodes of rigidity or posturing (abnormal body movements in response to brain injury).

PAID is generally seen in low-functioning head-injured patients in the ICU and rehab setting. It’s treated with medications to manage the symptoms, including muscle relaxants, beta blockers to lower heart rate, anti-hypertensive medications, and more. PAID can persist for months in these patients, and those who have it generally have head injuries so severe that they rarely return to full function. PAID seems like the less likely of the two possibilities, mostly because Bailey was awake within about two weeks of the injury, and went on to lead an essentially normal life.

Ace Bailey suffered a significant head injury by 21st century standards. The fact that he did it in 1933, had serious complications, and lived a full life afterwards is frankly amazing. An injury like this is unlikely now given the mandated use of helmets, but as we’ve seen in all the players whose lives and careers have been permanently affected by concussion, it doesn’t take a broken skull to change things forever.